Employees can be quite complex when it comes to how they approach learning in the workplace. They have all sorts of motivations and can make surprising decisions based on various influences, all of which can make it especially difficult for organisations to affect behaviour change.

The trick to really engaging employees around professional learning and development, to get them to take ownership of their own learning, is getting inside their heads. By applying behavioural economics, enterprise learning leaders can really start dissecting (figuratively) the way employees think.

What is behavioural economics?

Behavioural economics applies psychology, neuroscience and microeconomic theory to the study of individuals’ and institution’s economic decisions. If we view learning as an investment of the learner’s time, then behavioural economics can help an organisation’s learning leaders explain and predict learner behaviour. The salacious secret behind it is that people, on average, aren’t great at making decisions. Behavioural economics focuses on why people make the decisions that they do. It uses variants of traditional economic assumptions—often with psychological motivation—to explain and predict people’s behaviour by understanding their thought processes, which includes their internal biases and how they ultimately influence their decision-making.

How does behavioural economics apply to learning and development?

When you get right down to it, corporate learning is frequently about influencing behaviour change. Behavioural economists are interested in studying how people think about the decisions they make, often by bringing to light what may be subconsciously influencing people’s choices. Learning leaders can benefit from understanding these motivations so that they can affect behaviour change in their organisations.

According to Daniel Kahneman, a prominent, Nobel Prize-winning psychologist and behavioural economist, people have a predisposition towards being irrational. So, to combat that, he suggests thinking about thinking—considering how people’s minds are habitually contradictory, distort data, and mislead them.

In his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman identified two types of thinking that can help in that endeavour:

System 1 thinking

- Involves the mental processes that read emotions and handle automatic skills.

- It’s fast, automatic, frequent, emotional, stereotypic and subconscious.

- Example of System 1 thinking: seeing that an object is at a greater distance than another.

System 2 thinking

- Involves the mental processes that take a more methodical approach and use more formal logic.

- It’s slow, effortful, infrequent, logical calculating, conscious.

- Example of System 2 thinking: complicated math, or digging into your memory to recognise a sound.

Both types of thinking can inform how an organisation’s learning leaders design and engage employees around a professional learning and development experience. Ultimately, says Kahneman, making good decisions depends on paying attention to where information comes from, understanding how it’s framed, assessing one’s own confidence about it, and then gauging the validity of sources (system 2 thinking).

What learning leaders need to be able to do is figure out how to get employees to think that way when it comes to making decisions about workplace learning.

There’s a core theory of behavioural economics Kahneman, together with Amos Tversky, created that learning leaders can use to positively affect employees’ decision-making when it comes to learning:

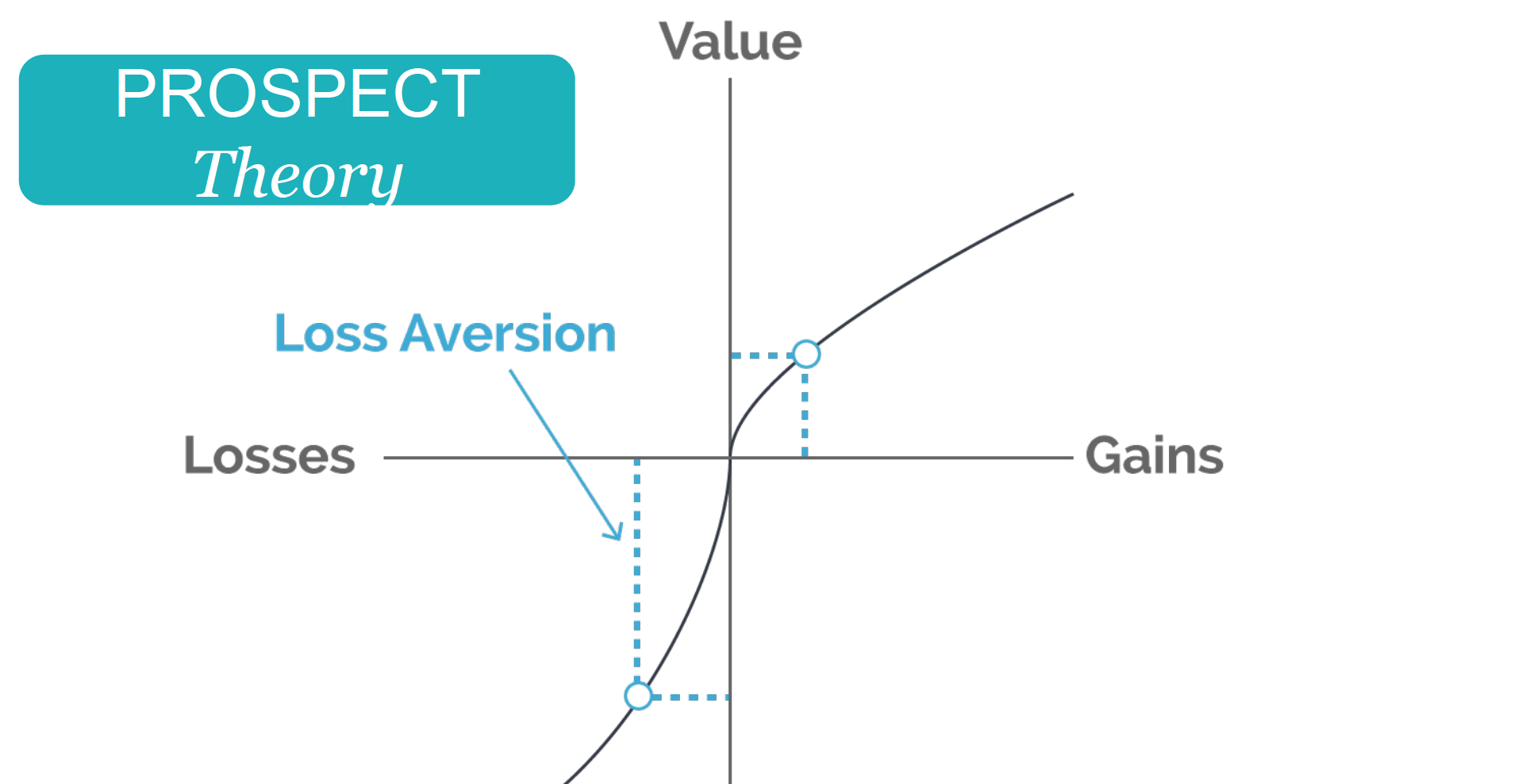

Prospect Theory

Prospect theory describes the way people choose between probabilistic alternatives that involve risk, where the probabilities of outcomes are unknown. The main principle is, essentially, that it hurts much more to lose something than it does to gain something—people tend to make bad decisions because they lose something and follow up with more bad decisions because of that pain.

Learning leaders can use prospect theory to engage employees around learning and development by highlighting the potential pain of standing pat in their current situation rather than selling them on the potential benefits—how are things like automation and artificial intelligence going to affect jobs and future employment? By speaking to what employees stand to lose, learning leaders can more effectively encourage employees to take ownership of their learning.

As learning leaders use behavioural economics to understand their learners’ motivations and thinking, they can help learners invest the time in learning and positively affect behaviour change to apply the learning on the job. After all, the aim of learning is not just to engage learners, but to have them use the new skills in their jobs and help the organisation move forward.

Sources:

Laibson, D., & List, J. A. (2015). Principles of (Behavioral) Economics. American Economic Review, 105(5), 385-90.

Lewis, M. (2016). The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed Our Minds. W.W. Norton & Company.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Thaler, R. H. (2015). Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics. WW Norton & Company.

Freakonomics Radio Podcast (Audible/Google Play/iTunes/Spotify

Written by

Jon Paul is a content marketing manager at D2L. He’s into writing, creativity, content, advertising, marketing, tech, comics, video games, film, TV, time and space travel.

Stay in the know

Educators and training pros get our insights, tips, and best practices delivered monthly